How serverless browsers unlock scalable web automation

Anyone can automate a browser. Doing it reliably and at scale, however, can be incredibly painful. Let me dig into this gap, and what changes for the better when you stop hosting browsers yourself.

Copy linkBrowser automation still sucks, at scale

In theory, browser automation seems simple enough: spin up Chromium, point it at a page, automate a few page interactions like scrolling or clicking buttons, and then collect the results. Easy, right?

Wrong. If we’re being honest, the first time I get a script working locally, it feels simple. This is exactly why the issue of scaling web automation is so demoralizing. I ship it, wire it into CI, and relish in the dopamine hit of a week of green runs. Then one random morning, unaware of my impending doom, I’ll open my laptop to a wall of red, despite zero code changes.

My logic didn’t break, but Chromium starts going haywire once you move it into containers and shared cloud runners. Well, of course it does - your laptop has a full desktop stack, stable fonts, a GPU, predictable RAM for your one job, and OS behaviours you know like the back of your hand.

Then you play a completely different hand: CI changes the OS, the resource envelope, and the Chromium binary in subtle ways, and Chromium is sensitive enough that those subtleties turn into flaky automation. When people say “automation is brittle,” this is what they mean when you end up debugging the runtime instead of the script. It’s frustrating because you did everything “right” and the environment still changed underneath you.

Copy linkWhy things start falling apart

Chromium is architected as a multi-process system. Even a single tab fans out into browser, renderer, GPU, and network processes, and cross-origin iframes often land in their own renderers too. That design is great for security and crash isolation, but in automation, it means one browser is really a small swarm of OS processes competing for resources. Modern pages amplify this because they’re iframe-dense by default (ex., ads, analytics, embeds, auth widgets), so a seemingly simple navigation can secretly become dozens of renderer processes doing layout, JS, and painting in parallel. On a high-RAM dev laptop, that overhead is basically invisible. In a virtual machine with tight CPU shares and a couple of gigs of RAM, the difference between something working and timing out forever becomes evident.

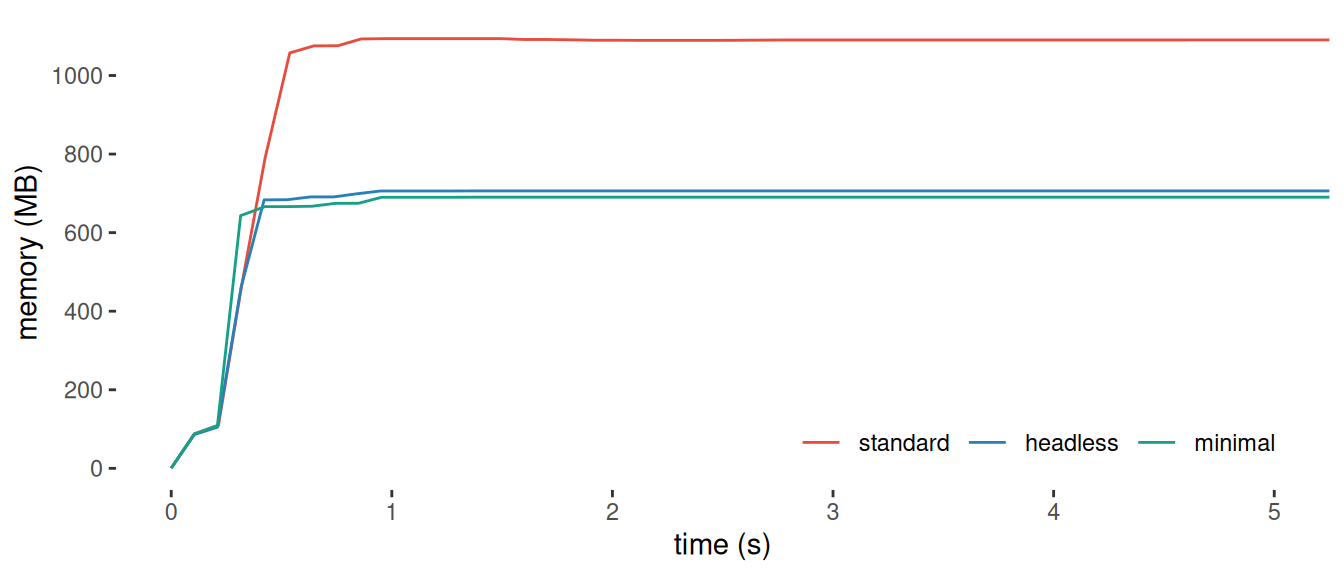

Scaling hurts because Chromium is already fighting memory pressure on normal modern websites with pages constantly allocating big JS heaps and DOM state, and not all of it getting cleaned up. In UI-less (headless) automation, you stress those paths harder with rapid navigations, repeated reloads, screenshots, tracing, and long-lived sessions. So when you run lots of sessions or long-lived automations in parallel, that baseline memory churn turns into real RAM growth and instability. In fact, Chromium runs have been reported to steadily eat RAM or fail to release it until the process is killed. In one experiment, a single Playwright/Chromium instance peaked around ~700MB-1GB, which is fine once, but terrifying at 50x parallelism.

Total memory consumption via Chromium (Source)

Total memory consumption via Chromium (Source)

Going from a few browsers to dozens doesn’t necessarily introduce a new class of bugs since it’s just multiplying the same CPU, memory, and process overhead until the VM hits its limits. At that point, the system starts degrading in predictable ways when the network calls slow or fail, your automation waits drift, and eventually the OS kills a Chromium renderer when memory runs out.

This is the moment where race conditions show up “for no reason.” Not because the web suddenly got nondeterministic, but because your timing assumptions were made on unconstrained hardware, and now the browser is fighting for oxygen.

TL;DR: the automation logic can be taken care of by a skilled developer and existing automation frameworks. The reason browser automation still sucks at scale is that you’re trying to run a complex, resource-hungry, multi-process rendering engine in environments it wasn’t designed to live in, and then asking it to behave like a deterministic function.

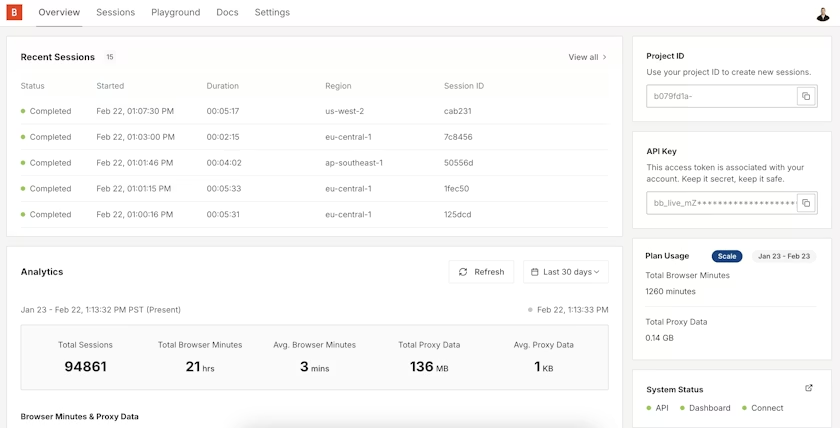

Try this interactive browser infra demo:

We’re asking for a little too much. So, we end up doing a lot.

You end up building a second system whose job is just to keep the first one alive with custom Docker images, pinned Chromium builds, cleanup scripts, CI hacks, “known good” flags, Slack threads full of “why is this failing now?” and defeatedly accepting a certain amount of flake as the cost of doing business.

After you do that long enough, you (hopefully) start asking a very pragmatic question that has nothing to do with scraping or testing and everything to do with ownership: why the hell am I running browsers at all?

Here’s an idea: just stop managing them.

Copy linkWhat are serverless browsers, really?

If running Chromium yourself keeps turning into an infrastructure project, the obvious question is what it would look like to keep the automation and outsource the runtime.

I present to you: serverless browsers.

It’s the same Chromium engine, the same DevTools protocol, the same Playwright or Stagehand code you already write, but the browser lives in someone else’s cloud instead of on your laptop or inside your Docker images. Instead of babysitting that environment, you ask an API for a fresh, isolated browser hosted in the cloud, connect to it over CDP, run your script, and then throw the whole thing away.

It’s browser infrastructure as a service. I get clean, ephemeral, single-use environments that spin up fast, behave consistently, and disappear when I’m done. There are no machines to provision, no containers to update, no Chromium binaries to pin or patch, and no browser-state to clean up. Instead of launching a local browser, you’re dialing into a preconfigured Chromium instance whose entire job is to execute your automation once and then vanish.

It feels surprisingly natural in practice because the automation scripts don’t change. You still write:

Stagehand script:

import { z } from "zod/v3"; import { Stagehand } from "@browserbasehq/stagehand"; (async () => { // Initialize Stagehand const stagehand = new Stagehand({ env: "BROWSERBASE", apiKey: process.env.BROWSERBASE_API_KEY, projectId: process.env.BROWSERBASE_PROJECT_ID!, model: "openai/gpt-4o", // Your OPENAI_API_KEY is automatically read from your .env }); await stagehand.init(); const page = stagehand.context.pages()[0]; await page.goto("https://docs.browserbase.com"); // Preview an action before taking it const suggestions = await stagehand.observe("click 'Stagehand'"); // Take a suggested action console.log(suggestions[0]); await stagehand.act(suggestions[0]); // Read the NPM install command const { npmInstallCommand } = await stagehand.extract( "Extract the NPM install command", z.object({ npmInstallCommand: z.string(), }) ); console.log(npmInstallCommand); await stagehand.close(); })().catch((error) => console.error(error.message));

Playwright script:

// Attach to an existing Chromium instance via the Chrome DevTools Protocol // (this can be local, remote, or serverless) const browser = await playwright.chromium.connectOverCDP( "http://localhost:9222" ); // Reuse the default browser context created by the remote instance const defaultContext = browser.contexts()[0]; // Grab an existing page (or create one if needed) const page = defaultContext.pages()[0]; // From here on, this behaves exactly like a locally launched browser

The automation code doesn’t really change, but the execution model does. Instead of spawning a local Chromium process and inheriting whatever your host environment happens to look like, you request a remote Chromium instance and attach to it over CDP the same way Playwright or Stagehand already does. The browser is provisioned per task, isolated to that task, and torn down when the session ends. In other words, the things you’ve been encoding in Dockerfiles, shell scripts, and CI configuration move out of your deployment surface and into the platform boundary.

That shift matters because most of the failure modes you fight at scale are runtime failures, not automation failures. When you host browsers yourself, you end up solving two intertwined problems at once: both writing correct automation and keeping a fleet of Chromium processes stable under load. With a serverless model, the second problem is externalized. Your code’s unit of work is mapped from one task → one fresh browser, which is a cleaner abstraction for parallel systems than X number of tasks sharing Y number of long-lived browsers on some machine.

Okay … so isn’t that just a cloud browser? Not quite. A cloud browser is a browser running somewhere else. A serverless browser is a browser you don’t run at all.

Let’s talk about what changes once you drop that responsibility.

Copy linkWhat actually happens when managing browsers is no longer your problem

Once new browser instances are spun up and torn down per run, state becomes explicit instead of accidental. Every task starts from a clean profile with no previous cookies, storage, or service worker residue. That alone removes a big class of heisenbugs where a test passes or fails depending on what ran earlier. When something does fail, you can usually attribute it to the script or the target site rather than to leftover browser state.

Concurrency also becomes a queueing problem instead of a hardware-tuning problem. In other words, you’re not deciding how many browsers a specific VM can tolerate before Chrome starts thrashing. You’re deciding how many tasks you want to run in parallel, and the platform maps that onto independent browser instances. The practical effect is that your concurrency limit is set by throughput goals and cost, not by whether a particular machine has 3 GB of RAM left.

Viewing all concurrent browser sessions in one dashboard

Viewing all concurrent browser sessions in one dashboard

Don’t get me wrong, browsers still crash (I fear that’s unavoidable), but a crashed instance won’t jeopardize the rest of your job anymore. If a renderer dies, it takes down that one task’s browser, not a shared pool. Recovery is just a “new instance, same task” rather than digging through a hung machine to clean up Chrome’s mess. This makes long-running workflows easier to reason about, since failure becomes per-task and restartable instead of systemic and sticky.

Network configuration moves in the same direction. Instead of engineering routing, proxy rotation, and regional outbound traffic as part of your own infrastructure, you request the network properties you need for a task and treat them like parameters. The browser runs with that outgoing network and isolation, and your automation remains the same.

Stagehand script:

import { Stagehand } from "@browserbasehq/stagehand"; const stagehand = new Stagehand({ env: "BROWSERBASE", apiKey: process.env.BROWSERBASE_API_KEY, projectId: process.env.BROWSERBASE_PROJECT_ID, browserbaseSessionCreateParams: { proxies: true, region: "us-west-2", browserSettings: { viewport: { width: 1920, height: 1080 }, blockAds: true, }, }, }); await stagehand.init(); console.log("Session ID:", stagehand.sessionId);

Finally, good riddance to Chromium maintenance. You’re no longer tracking Chrome builds against Playwright versions, not adjusting sandbox flags per base image, and not rebuilding Docker layers when a system dependency changes. The browser runtime becomes an external dependency with a stable interface (CDP), and your scripts run against that interface rather than against your own carefully-maintained environment.

Copy linkA love letter to serverless browsers

Serverless browsers are compelling less because they’re novel and more because they align browser automation with the rest of modern compute. A browser becomes an ephemeral unit of execution: allocate, attach, run, dispose. You still write Playwright or Stagehand exactly the way you already do, but the operational work of keeping Chromium healthy under cloud constraints is no longer mixed with your automation logic.

Serverless feels obvious in hindsight, but it only becomes the clear solution after someone trudges through the unglamorous work you’ve been putting up with for years. They must take Chromium seriously as production infrastructure, customize it for headless reliability and scale, and then operationalize it as a cloud-native runtime with sane isolation, networking, and lifecycle semantics.

That’s the part many teams never want to own long-term, because it’s a tax that keeps compounding. At Browserbase, we bet that this tax should live in one place, rather than every company’s CI and Dockerfiles.

If that resonates, don’t overthink it and start writing automation that scales: npx create-browser-app.