This week we fixed the worst part of Browserbase

This week we fixed the worst part of Browserbase.

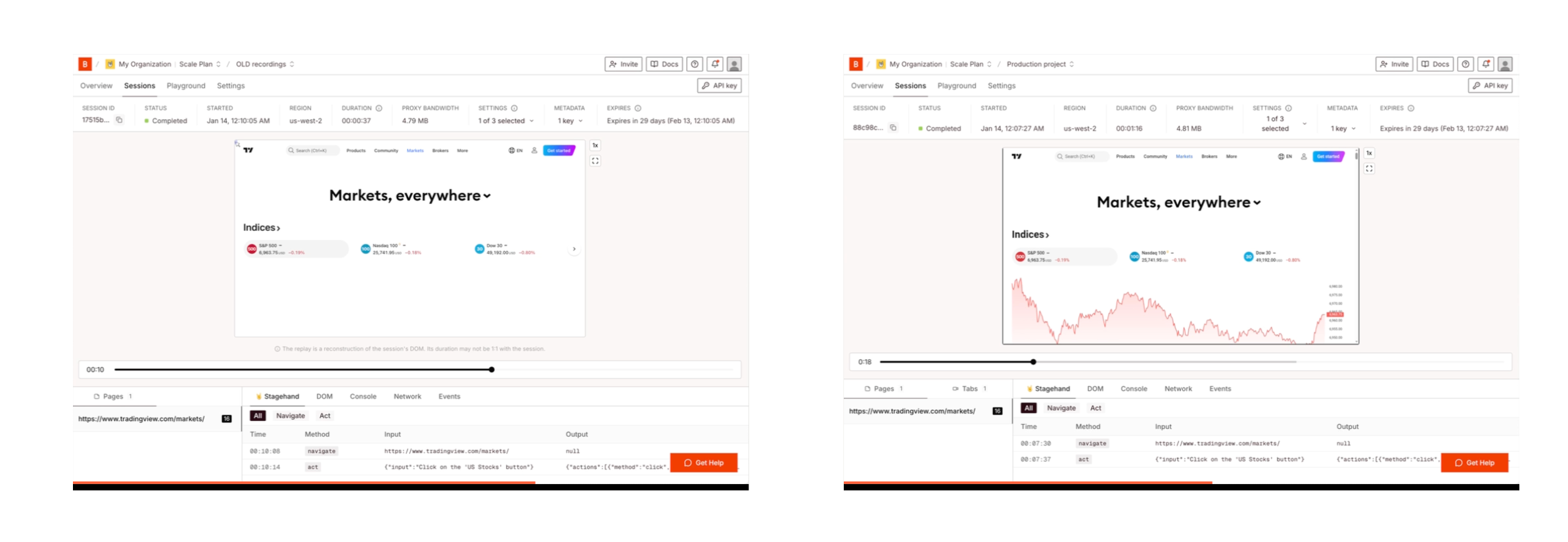

I’m not clickbaiting you either. For a long time, session replay was the weakest feature in our product. People tried it, got confused or frustrated, and stopped trusting it.

The irony is that we should have known better.

Recording what happens on a screen and showing it back to you accurately is not a new problem for many of us on the team. But at Browserbase, we deliberately tried something different. Instead of recording pixels, we used a library called rrweb to capture DOM mutations (HTML, CSS, and user events) and replay them later.

On paper, this looked elegant. It was cheaper to store and it avoided video encoding. It felt more “web-native.”

In reality, it constantly broke.

Websites don’t agree on how to represent HTML and CSS. Nested iframes, shadow DOM, canvas elements, and video players all push DOM-based replay past its limits. The replays would be incomplete, incorrect, or subtly wrong. Worse, they often looked correct at first glance while lying about what actually happened.

At some point, our conclusion became unavoidable: the easiest and most reliable way to show what happened in a browser is to just record what was on the screen.

So we’ve rebuilt exactly that.

This post explains how we rebuilt session recordings from scratch, why we made the architectural choices we did, and how we turned what used to be our weakest feature into something we’re confident putting in front of the most demanding users.

Copy linkWhy DOM reconstruction fails in the real world

rrweb works by observing DOM mutations, serializing them as events, and replaying those events later to reconstruct page state. The idea is clever. In a controlled environment, it can even be more semantically correct than video. You’re replaying intent, not pixels.

The problem is that the web is not a controlled environment. 🤷♀️

Nested iframes break this model almost immediately. An iframe is a document boundary. Nest them deeply enough (which real applications do) and you end up with parts of the page that the recorder can’t see, can’t reason about, or can’t reliably replay. We saw sessions where large sections of the page simply didn’t render during replay.

Canvas, WebGL, video elements, shadow DOM - anything that isn’t “normal” HTML becomes either flaky or invisible.

Even when replay does work, it can lie in subtler ways.

Replay a session days later and you might see today’s data instead of what was on screen at the time. A weather widget updates, the clock advances, or perhaps an API response changes. rrweb faithfully replays DOM instructions, but the environment has moved on.

That mismatch destroys trust. As developers, we don’t look at session replays for vibes. We look for causality.

At some point, our conclusion became unavoidable: the easiest and most reliable way to show what happened in a browser is to just record what was on the screen.

Copy linkRecord the screen, not the theory of the screen

Our new system records what the browser actually renders.

At the core is a Chrome DevTools Protocol (CDP) screencast that captures screenshots of the browser viewport. Conceptually, it’s the simplest possible thing: take a picture of the screen whenever it meaningfully changes.

Not at a fixed frame rate, and not 60fps for the sake of it. If nothing changes for ten seconds, we capture nothing. If the page is animating, we capture more.

Each frame is timestamped with sub-second precision.

We deliberately capture frames as PNG, not JPEG.

JPEG compression is lossy and CPU-intensive, so the video compression is worse. We want the browser doing as little work as possible so it can focus on the customer’s automation, not our observability pipeline. PNGs are larger, but they’re fast to produce and lossless. We stream them off the browser immediately. Nothing resembling video encoding runs anywhere near the browser.

Copy linkAsynchronous encoding and constant-time recordings

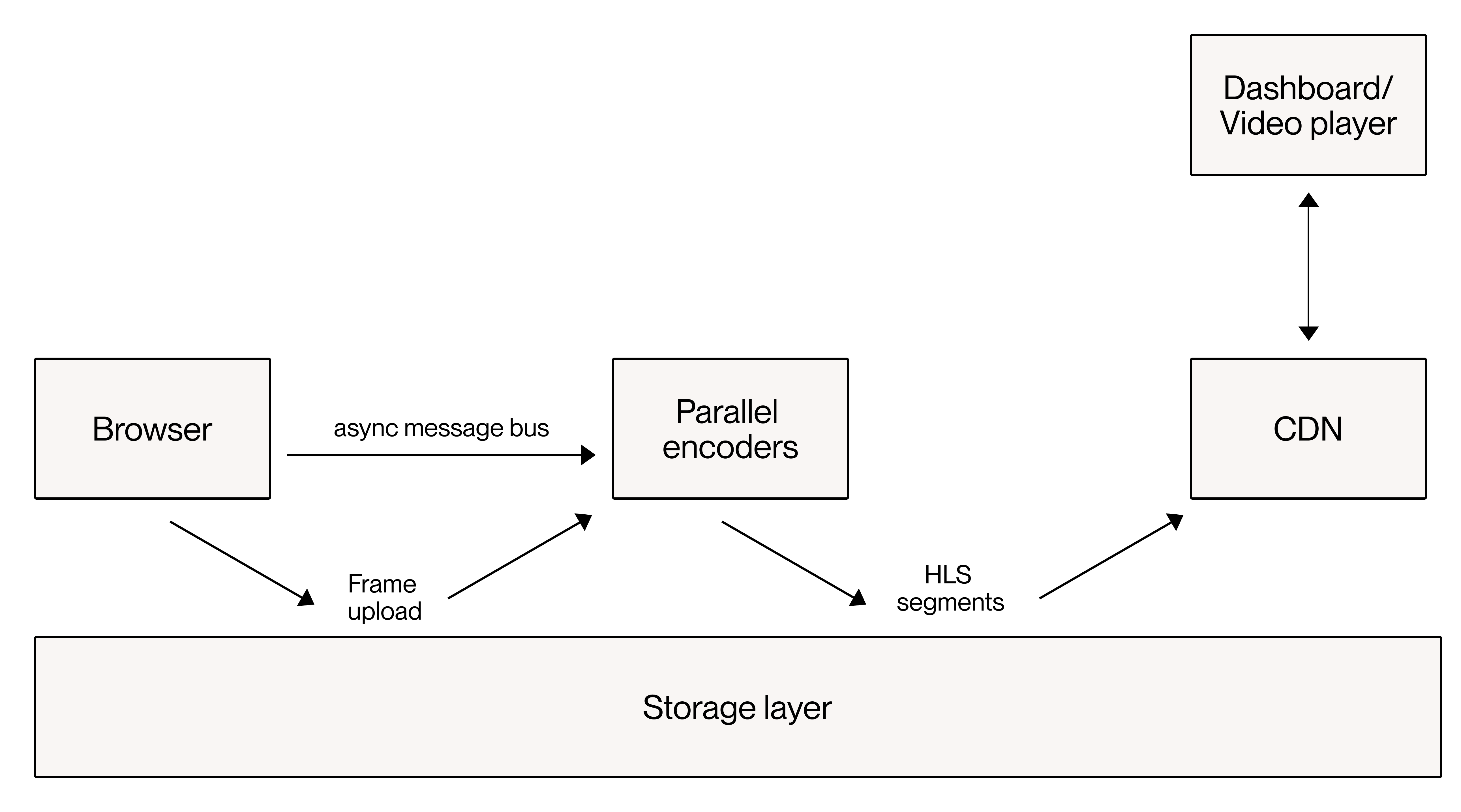

Now, what we end up with is a stream of timestamped PNGs per tab.

Turning that into video is computationally expensive, so we do it asynchronously as frames land in object storage. Every ten seconds of session time, the browser emits a message indicating a segment boundary.

Encoder workers consume those messages, pull the frames, and independently encode a ten-second HLS fMP4 segment using H.264.

This gives us a non-obvious property: encoding time is independent of session length. A six-minute session and a six-hour session take roughly the same wall-clock time to become playable, assuming enough workers, because all segments can be encoded in parallel.

This is also why we never used WebRTC. Anything that compresses video in the browser steals CPU from the workload. Hard pass on that. 😬

Copy linkBinary surgery on fMP4 segments

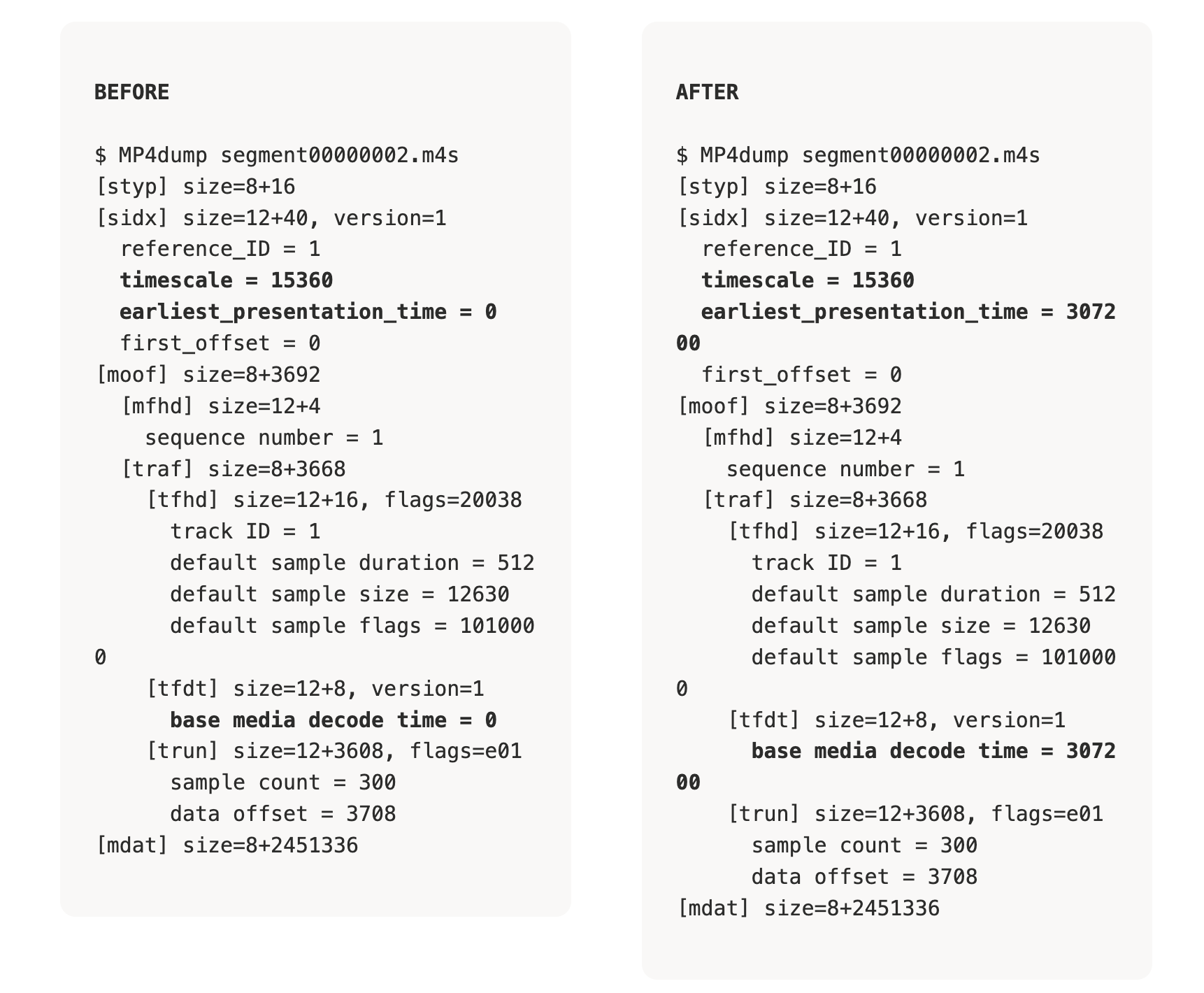

But, parallel encoding introduces a timing problem. ffmpeg encodes every fMP4 segment as if it starts at time zero. There is no flag, filter, or muxer option that fixes this for HLS.

So we patch the files!

After encoding, we open each segment and overwrite the timing fields directly (earliest_presentation_time and base_media_decode_time) with the correct offset derived from the segment index and timescale. Once patched, the segments stitch together seamlessly.

It’s byte-level surgery. It’s blunt, and she’s perfect. 🤌

Copy linkHLS as an delivery primitive

We deliver recordings using HLS.

HLS gives us chunked delivery, instant seeking, and CDN-friendly caching. Players request a playlist, then pull segments just ahead of the playhead.

This is an observability problem, and HLS turns out to be a pretty great observability transport.

Copy linkMulti-tab recordings without flattening reality

We record up to ten tabs simultaneously.

Each tab is captured and encoded as its own stream, but all streams share the same global timeline. This is represented using an HLS multi-variant playlist. Normally variants mean bitrates, but we repurpose them to mean tabs.

Switching tabs in the recordings UI is switching variants, without changing the timestamp.

If something happened in a background tab while you were interacting with another one, you can actually see it. It’s not a guess.

Copy linkSecure playback, segment by segment

Session recordings are sensitive.

The playlists are generated dynamically. Every segment URL is signed with a short-lived token, and validation happens at the CDN edge. The tokens expire, old links die, and authorization is enforced per segment.

The player doesn’t know. It just plays video.

Copy linkCost, scale, and just-in-time encoding

Encoding video is expensive. Encoding video no one watches breaks the bank.

We encode everything, but only roughly 8% of sessions are ever replayed.

The new architecture supports just-in-time encoding: eagerly encode the first ~30 seconds so playback starts instantly, then encode the rest only if someone actually watches.

Because encoding is parallel and constant-time, even a six-hour session can be made watchable quickly when requested. The tradeoff is brief buffering when jumping to unseen regions, which we’ve deemed acceptable for debugging.

This is how we get reliability and reasonable economics at scale.

Copy linkWhat this unlocks going forward

Once we stop pretending a replay is a DOM simulation and treat it as a real recording, a lot of problems disappear.

The timing becomes deterministic, multi-tab behaviour is understandable, exporting a recording seems trivial, and retention turns into a storage problem instead of a data-modelling problem.

It also simplifies the browser itself. We run less code inside customer sessions than before. There’s no mutation observers injected into pages, or recordings-specific logic racing application code. The browser does one thing: render pages. We observe the result.

Session recordings is rolling out now for Browserbase customers.

If you tried our old session replays and hated them, this session recordings rebuild is for you.